Visualizing Personhood and Dignity, or the Art of Mattering

Sean Kramer

University of Pittsburgh

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.Universal Declaration of Human Rights,

General Assembly of the United Nations,

resolution 217 A (III)1

The opposite of dispossession is not possession. It is not accumulation. It is unforgetting. It is mattering.Angie Morrill, Eve Tuck, and the Super Futures Haunt Qollective,

“Before Dispossession, Or Surviving It,” 20162

Introduction

We live today in a splintered world. One of the most extensive ruptures—which tears right down the seam of our contemporary existence—is the one between real, lived experiences and the representations of those experiences through the news, social media, entertainment, and yes, even art. Scholars in a wide range of academic disciplines have explored and continue to explore that separation, which seems to be growing. Another major source of division involves the way certain lives are framed by means of those forms of representation. Philosopher and scholar Judith Butler potently argues that media, culture, and political discourse frame certain lives as living and therefore worthy of grieving while others are marginalized, often because of their race, ethnicity, gender, or class.3 This phenomenon manifests itself perhaps most intensely during times of conflict. Butler’s thesis resonates in distinct ways in a number of cultural and political discourses unfolding in the present moment: for instance, one might note the stark contrast in how Israeli and Palestinian lives and deaths are framed in the current conflict, which often varies by news source.4 One might also consider the valorization of sacrifice and patriotism that characterizes Ukrainian resistance to the Russian invasion in contrast to the occlusion of most if any mention of the ongoing violence in Congo and Sudan. In the United States in recent years, commentators have decried a seeming fixation on brutality and shock in regard to anti-Black violence perpetrated by law enforcement.5 In these diverse arenas, the urgency to verify and call out the enormity of violent acts—often state-sponsored if not state-enacted—is now being measured against the agency of the individuals and communities affected by that violence as well as their consent to be depicted in often-dehumanizing circumstances.

The multipart project Irreplaceable You: Personhood and Dignity in Art, 1980s to Now, presents some of the strategies with which contemporary artists have addressed the complex pictorial and ethical dynamics around the representation of violence, catastrophe, and systemic oppression over the past four decades. These artists grapple variously with pain, fear, and loss, but many of them also seek out joy, creativity, and worth amid distressing or overwhelming circumstances. Their work has incredible poignancy in light of the rise of the twenty-four-hour news cycle and the advent of the Internet, both of which have contributed to our unavoidable exposure to imagery meant to shock or dismay. The artists featured in the exhibition use diverse media as they engage with social and political issues in a wide range of geographical contexts. Employing strategies like portraiture, storytelling, naming, and sometimes even using traces of their own bodies, these artists actively resist the seemingly all-pervasive power of the virtual sphere to transform lived human experiences into objects of consumption, data sets, or algorithms. The aim of this project is not to provide a comprehensive survey of a defined field of artmaking. Rather, it stages a series of interventions and moments of contemplation, prompting visitors to negotiate the ambiguities between empathy and dehumanization, visibility and spectacle, safety and precarity that pervade our current visual culture and public discourse.

In what follows, I offer some context and insight into the curatorial thought process and research that went into the development of this project. One challenge I have found myself working through is how to give shape to rather complex ideas while allowing the individual artworks space to breathe. We curators and art historians love our periodization, categories, and explanations. So, to let the questions and contradictions raised by this group of objects remain open to discussion is in itself a break from certain institutional and disciplinary conventions. Even so, one needs a common ground for discussion. Therefore, the next section of this essay puts forward some (flexible) definitions for the terms “personhood” and “dignity,” outlining how I have approached them over the course of this project. Following this reflection on terms, I present three broad issues that artists featured in the project bring to our attention: 1) the curious aesthetic and even libidinal pleasure in violence promoted by the news and social media; 2) the use(s) of empathy as a form of social and political resistance; and 3) the means through which art, as an idea, as an institution, and as a social practice, has the capacity to bestow or withhold dignity from persons and objects. This essay triangulates such issues amid an overburdened visual economy that comprises numerous often-competing arenas of production and reception, including journalism and activism; media, social media, and entertainment; and the spaces of art, including the museum, gallery, and fair. As examined below, this visual economy has long been white dominated. While this essay and the exhibition can’t necessarily offer resolution to many of the profound questions and problems they themselves raise, the goal of this project is to help us grapple with and confront such complicated and contested histories.

Personhood and Dignity: Why These?

The terms “personhood” and “dignity” kept surfacing as I was thinking through the cultural and societal tensions laid out above. These are terms frequently repeated in the language of journalists and commentators when addressing systemic and racial violence, and I came to wonder how they may map onto contemporary artistic concerns. Personhood and dignity are capacious concepts that resist easy categorization, especially in relation to art. Both encompass diverse meanings and associations, which are by-and-large shaped by Western scholarship and social practices. As such, they overlap with and diverge from equally broad and multivalent concepts of humanity, difference, and empathy. One can often (though not always) tell whether a work of art depicts a human subject.6 One might also be able to tell whether a work of art depicts its subject in a dignifying way. But attempting to define a unifying set of pictorial and conceptual parameters around “personhood” and “dignity” raises several questions. For instance, what would an aesthetics of personhood look like? What would constitute its primary visual markers?

Similar questions might be asked of dignity: we may recognize it when we see it, but could we agree on a set of formal criteria for it? Does dignity mean the same thing to all people, in all places, and at all times? Of course, the answer to this last question is no. But in response to the other questions: the project of Irreplaceable You puts divergent strategies and practices in conversation to see what lessons might be gained from sometimes surprising juxtapositions, rather than striving to define a cohesive visual style, artistic movement, or national school. The goal is in fact to surface these kinds of questions—questions that have aesthetic, theoretical, and real-life ramifications—rather than to find end-all, be-all solutions to them.

It may not be surprising that scholars in a wide range of disciplines have examined the concept of “personhood” and have had trouble reaching a unified explanation.7 For our purposes, we might conceive of personhood broadly as habits of thought and sets of performances, encompassing both inward-facing understandings of the self and outward-facing behaviors, interactions, and relations with others. Naming, a sense of place, and group belonging all play important roles in both psychic and social constructions of the self, pinpointing our roles and status in society and giving shape to our inner conceptions of identity. Personhood is also contextual and shifts depending on changes in environment and at different stages in one’s life. The status of the individual vis-à-vis the state, specifically the state’s power to regulate bodies and populations, has preoccupied scholars for decades and has heightened urgency today.8 Of intense concern in the United States in the present moment is the state’s authority to confer personhood on non-sentient entities like corporations, artificial intelligence, and embryos, while denying personhood to individual and categories of human beings, whether through legislation, violence, or political rhetoric.9

“Dignity” is no less an ambivalent and ambiguous concept. To form a working definition of it, we may start with some of those provided by the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, which include “formal reserve or seriousness of manner, appearance, or language;” and “the quality or state of being worthy, honored, or esteemed.”10 Implicit in these definitions is the understanding that dignity is agreed on if not bestowed. These two dictionary definitions insinuate that human subjects are among those deemed as “worthy, honored, or esteemed,” which may recall the United Nations “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” quoted at the outset of this essay. People, cultures, and societies frequently assign value to objects or treat them with respect; a location where this regularly occurs is in the art museum, a phenomenon explored in the final section. We may be tempted by these definitions to claim that all human life is worthy of dignity—as the United Nations declaration in the epigraph states—yet the history of human social relations has given evidence that this is far from a universally shared view. Scholars and philosophers such as Giorgio Agamben, Judith Butler, Maggie Nelson, Achille Mbembe, and others have examined the contradictory standards with which human life is regarded, concluding that these are baked into the very foundations of the modern world.11 As artists in Irreplaceable You point out, conditions like homelessness, incarceration, refugeeism, and sex work, along with certain racial, ethnic, and gender identities, have through dominant social and political formations been framed as less or even un-worthy of dignity.

The “Aesthetic Pleasure” of Violence

I move now to a discussion of systemic violence in the media and visual culture because that is one phenomenon with which several artists in Irreplaceable You engage. The exhibition registers a shift in how systemic violence is both referenced and depicted in contemporary visual culture. The history of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries is replete with examples of the mass proliferation of photographs and video footage of torture, mutilation, homicide, and other forms of immense terror and pain meeting with inaction at best, censorship and retaliation at worst.12 We may consider, for instance, the videos and photographs that made evident the atrocities committed by American soldiers against Iraqi prisoners in Abu Ghraib in 2004. On one hand, the public attention through media reports and imagery was a caesura; it momentarily interrupted the official narratives of American suffering and liberation and suspended any ability to ignore the all-encompassing brutality of one nation having laid waste to another. As with imagery of other atrocities in history, the footage from Abu Ghraib was framed as imperative: if only the people knew, then there would be no way a society that prides itself on democratic ideals would allow such horrifying violations of human rights to continue.

Author Maggie Nelson is but one of numerous observers to realize the naivete underlying that assumption. In her book The Art of Cruelty, published in 2012, Nelson makes clear that the “model of shaming-us-into-action-by-unmasking-the-truth-of-our-actions cannot hold a candle to our capacity to assimilate horrific images, and to justify or shrug off horrific behavior.”13 As Nelson demonstrates, what has lately been framed as an uptick in cruelty in the social and political discourse of recent decades is not somehow an aberration but rather a symptom of a chronic condition. One of her incisive points is that television series like American Idol and 24 elicit a desire for witnessing cruelty that in turn primes us for consuming imagery and accounts of violence, conflict, and catastrophe in the news.14 Building on ideas put forward by media theorists such as Guy Debord and Jean Baudrillard, Nelson reminds us that news, entertainment, and advertising all inhabit the same media terrains: the newspaper, television, the computer, and now our phones.15 We may be immediately able to distinguish between violence occurring in the realm of a fictional show—scripted, costumed, performed, and produced—and the documentation—raw and unrehearsed—of real-life violence. But they still occupy overlapping fields of consumption. On any given day, we may be able to open a video that depicts the most horrific scenes of torture, mutilation, and death and then scroll casually to a meme about an episode from our favorite show that streamed last night.

Reading Nelson’s meditation on cruelty in 2024 produces the chilling realization that we have been living with this condition for a long time, and it is not limited to certain flashbulb moments of actual violence. What also has a long history is a tendency of certain viewers to derive aesthetic if not libidinal pleasure from witnessing violence. Viewers’ relationships to imagery and accounts of violence in the news and elsewhere are shaped by their backgrounds, political views, socioeconomic status, geographic location, and other aspects of their situated positions. For instance, the journalistic discourse around imagery of Black death and suffering, including the video footage of the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, viewed and shared online millions of times, calls attention to a troubling cultural fixation on the shock of violence. The motivations for that shock, especially among white viewers, have rightfully been called into question. In their work on nonviolence, Judith Butler has suggested how the singular events of unjustified killings, such as those perpetrated by law enforcement against George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Daniel Prude, Rayshard Brooks, and others, were in fact manifestations of broader systems at work:

Without disputing the violence of the physical blow, we can nevertheless insist that social structures or systems, including systemic racism, are violent. Indeed, sometimes the physical strike to the head or the body is an expression of systemic violence, at which point one has to be able to understand the relationship of act to structure, or system.16

The wave of protests that followed in the summer of 2020 responded as much to the loss of individual life as to the systemic violence and structural inequities of which that loss was a representative part.

American photographer and educator Joshua Rashaad McFadden (born 1990) makes the visual connection between a singular event and broader social and political forces in a work like I Can’t Breathe (Minneapolis, Minnesota) (2020; printed 2024) from his series Unrest in America. An expression encapsulating at once anger and dignity beams out from the eyes of the central figure, framed between two furrowed brows and a black cloth facemask inscribed with a Black Lives Matter logo. This central figure’s forceful gaze conveys the psychological intensity of a historical moment, the confluence of protest and pandemic, all while only seeing half the man’s face. Meanwhile, interlocking bodies form a wall, a phalanx, facing the photographer. Black t-shirts bearing the phrase “I can’t breathe” (George Floyd’s final words) combine with black beanies, black sunglasses, and black facemasks into a visual barrier, a force of resistance that refuses our visual or imaginary entry into the world depicted. We might imagine another phalanx marshaling behind us: the forces of the state, the police.

One might place in conversation with I Can’t Breathe the equally compelling photograph by McFadden, Tenderly Speaks the Comforter (2020) from the series Love without Justice. Here, two nude figures are depicted in bust format and close to the picture plane, establishing a sense of physical proximity between the viewer and the subjects. The strong contrast and backlighting obscure much of the detail on the two figures, making them appear almost to merge into one. Just behind them, a sheer white curtain veils a white-paned window, which provides a shallow backdrop to this quiet moment of queer intimacy and suggests a domestic interior. The title has a Biblical connotation, potentially referring to the alias given to the Holy Spirit in the King James Version of the Gospel of John and invoked in a verse from the Christian hymn “Come, Ye Disconsolate,” published in 1816 by Thomas Moore (1779–1852): “Here speaks the Comforter, tenderly saying, / ‘Earth has no sorrow that heaven cannot cure.’” The two heads nestling together visually suggest that one man may be whispering into the ear of the other, while the image’s poignant simplicity leaves ambiguous which one is the “comforter.”

McFadden’s deeply personal series Love without Justice explores quiet moments of connection and community through (often nude) self-portraits, portraits of family and friends, still lifes, and scenes of everyday life. These works evoke a sense of interiority and care that differs markedly from I Can’t Breathe. The formal differences between McFadden’s two images point to the manifold dimensions of Black experience in the United States, which McFadden seeks to convey through his separate but interrelated projects and which include but also go beyond violence and racial trauma. What this juxtaposition of protest and tenderness, of exteriority and interiority, makes us examine is one of the fundamental techniques of systemic violence and oppression: that is, the stripping away of agency and dignity through processes of dehumanization.17 The photographs refuse the possibility of dehumanization through their monumental scale, which forcefully declares their presence and makes them impossible to be ignored or avoided.

Iranian-British artist Reza Aramesh (born 1973) similarly makes us consider how we relate to images and accounts of human suffering in works like Action 247: At 11:45 am Friday 27 June 2003 (2023) from the series Site of the Fall –Study of the Renaissance Garden. This marble sculpture features a lifelike depiction of a young man who appears to have been stripped down with a garment or undergarment placed over his face. Aramesh engages with a long tradition of public figural sculpture—which are often life-size or larger than life-size—yet deliberately reduces the scale to encourage us to come in closely. The figure’s placement on a pedestal requires that we look up at his face. As with many of his works, Action 247 is both politically and erotically charged. The figure enacts a front-facing pose with one foot slightly ahead of the other, one arm to the side, and the other behind his back. While the upper half of the figure’s face has been sculpted to appear covered, the tilt of the head suggests an upward gaze. The naturalistic carving conveys the figure’s athletic physique as well as the convincing illusion of fabric wrapping around a body, of socks gathering at the ankles, of clothes piling at the feet. Through such visual means, the sculpture holds in tension the indignity of having one’s clothes forcibly removed, on the one hand, and the idealization and otherworldliness suggested by the light-gray marble, on the other. Also held in tension are the notions of violence and desire, a tension that, as the artist himself has noted, carries through Greco-Roman sculpture from classical antiquity as well as European devotional and mythological sculpture from the Middle Ages and later.

Violence as a caesura or a rupture informs Aramesh’s practice. As source material, Aramesh consults reportage imagery found online, in the news, and other archives that document conflicts occurring around the world from the 1960s to the present. The original “event” then undergoes several stages of mediation, first by means of the journalistic imagery, then through a reenactment of the scene by a studio model, then through the artist’s own photographs and three-dimensional scans, and finally by way of the marble sculpture. Aramesh often orchestrates large-scale interventions and performances in museum spaces like the Museum of Fine Arts in Havana, Cuba, and the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles, France; such jarring juxtapositions impel viewers in turn to consider the underlying systems of ideology and domination that have made such built environments possible. Recently, Aramesh has installed several over life-size standing figures as well as 207 lifelike marble depictions of underwear in the Chiesa di San Fantin in Venice, Italy, as part of the 2024 Venice Biennale. The sculptures reference the removal of the clothing of political prisoners, underwear often being the final element of dignity.18

While Aramesh’s and McFadden’s projects take up different paradigms with their own historical trajectories, both works arguably trouble our optical relationship with power and violence, requiring that we as viewers examine our own potential passivity or even aesthetic pleasure from witnessing atrocity. Both acknowledge that imagery and accounts of atrocity—whether in the context of police violence or neo-imperial conflicts—circulate within a white-dominated visual and cultural economy. Museums are part of this visual economy. Their spaces simultaneously present possibilities and limitations for considering themes of racial, colonial, gender, class, and other forms of violence. On the one hand, as a communal institution, a form of public sphere, the museum provides a space for contemplation and discussion of complex issues that may lack easy resolution. Still, the museum is structured by its own set of power dynamics, which in certain cases underscore rather than challenge the racial, colonial, gender, and class inequities that have made such violence possible in the first place.19 Like Aramesh, several artists in Irreplaceable You either intervene directly into the museum’s habitual framing of art, or they make it work for them.

Empathy as Resistance

One of the tacit or even consequent claims of this project is that the combination of personhood and dignity in art should promote empathy and, following Judith Butler, the recognition of life.20 Of course, there are varying kinds of empathy.21 The works centered here treat empathy as a sharing in both the sorrow and joy of other people whose identities, experiences, and backgrounds may or may not be quite different from our own. Empathy does not eliminate difference, but it erodes the fear of the other. What we are seeing in a culture increasingly focused on cruelty, tribalism, and resurgent ethnic nationalisms is that empathy—and even the recognition of certain lives—can itself be an oppositional political stance. Empathy proves a significant roadblock to power, as it renders difficult the kinds of division that make populations easier to manipulate or that help justify war, genocide, and other means of singling out individuals and collectives for destruction.22

In his book Necropolitics (2019), Cameroonian theorist and historian Achille Mbembe characterizes the current global political order as centered on death and division. He poignantly asserts that, “in the wake of decolonization, war (in the figure of conquest and occupation, of terror and counterinsurgency) has become the sacrament of our times in this the twenty-first century.”23 Mbembe’s meditation on decolonization and war articulates some guiding questions for this essay and the broader project of Irreplaceable You:

Can the Other, in light of all that is happening, still be regarded as my fellow creature?

When the extremes are broached, as is the case for us here and now, precisely what does my and the other’s humanity consist in? The Other’s burden having become too overwhelming, would it not be better for my life to stop being linked to its presence, as much as its to mine? Why must I, despite all opposition, nonetheless look after the other, stand as close as possible to his life if, in return, his only aim is my ruin?24

With this set of questions, Mbembe asks what happens to our sense of empathy, even our responsibility toward the life of the “Other,” including not only those different from us but also those who through conflict, politics, or circumstances are framed as our enemies. Mbembe’s open-ended questions leave it to us to decide who precisely is “the Other,” the one whose “only aim is my ruin.” The specter that haunts these questions arises, as Mbembe explains, from the combination of ethnic and racial nationalisms with the “law of the talion,” a tradition of justice based on retribution and vengeance that dominates legal systems, geopolitics, even personal worldviews, and perpetuates a seemingly endless cycle of violence.25 Mbembe suggests a possible way out of this cycle in the form of another question: “If, ultimately, humanity exists only through being in and of the world, can we found a relation with others based on the reciprocal recognition of our common vulnerability and finitude?”26

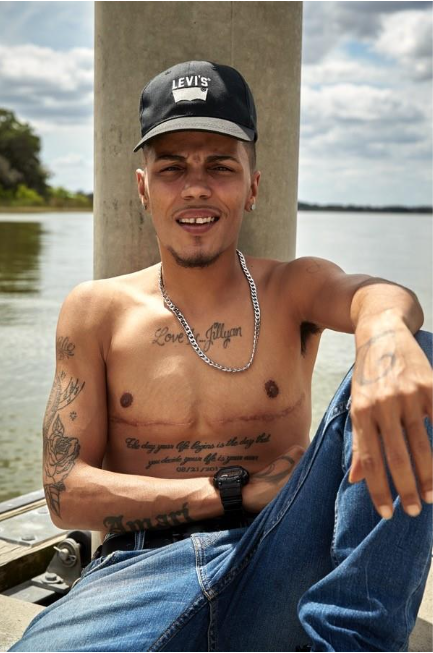

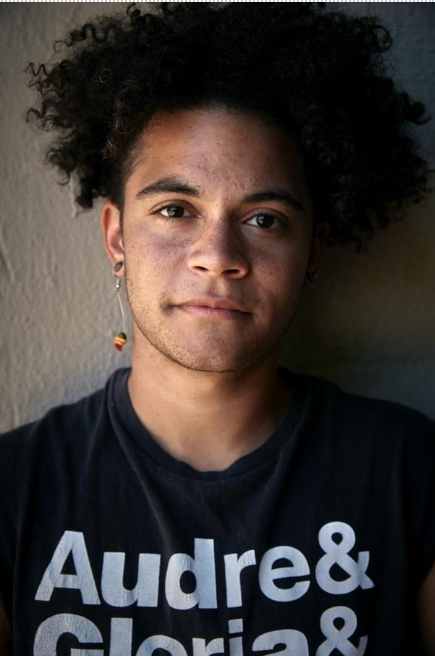

Australian photographer Soraya Zaman (born 1980) uses the medium of photography to counter legislative, rhetorical, and physical violence perpetrated against a vulnerable group: in this case, trans men living in the United States. Zaman’s series American Boys aims to present a cross-sectional representation of the transmasculine community across the United States and for which Zaman traveled to cities and towns in twenty-one states over a period of three years. The resulting photographic project does not dwell on vulnerability and violence per se but rather calls our attention to lives continuing, even flourishing, despite them. Working in a time when white nationalism has become intricately tied to transphobia, Zaman—who is based in the United States—encourages viewers to think critically about both Americanness and masculinity as structures of identification and as agreed-on social, cultural, and political formations, which are not at all innate categories but are historically and geographically specific and constantly negotiated and contested. The title American Boys plays on notions of masculinity, youth, and maturity. Four portraits from this series are included in Irreplaceable You: Amari (from Mount Dora, Florida), Teddy (from Kansas City, Missouri), Chella (from Brooklyn, New York), and Lazarus (from Albuquerque, New Mexico), all of whom the photographer had met through social media before traveling to meet them in person.27 Zaman’s full series, published into a book in 2019, includes multiple photographs of each sitter along with a written statement, ranging from a few sentences to a paragraph, in which the subject reflects on their personal journeys, worldviews, or the status of transness broadly conceived.

On a structural level, American Boys seems to align with what art historian Julian Stallabrass has termed a “neo-ethnographic” trend in contemporary photography.28 As Stallabrass has explained, nineteenth- and early twentieth-century ethnographic photographers often combined single-figure portraits with statements from their subjects in attempts to document various social types or raise awareness about groups marginalized by society.29 Such projects occupy an uneasy space between colonizing and humanitarian impulses. Zaman does take up the format of the individual portrait with an accompanying statement, which on the surface seems analogous with ethnographic photography. However, in American Boys, the elements of performance and the images’ differing formats interrupt the sense of uniformity and objectivity at work in ethnographic portraiture, with Zaman perhaps even reclaiming (consciously or unconsciously) a mode of image-making historically tied to classification and domination. Meanwhile, the inclusion of each subject’s pronouns in the title—a deliberate move by the artist in consultation with the sitters—redeploys another form of classification by giving the power to classify back to the individual.

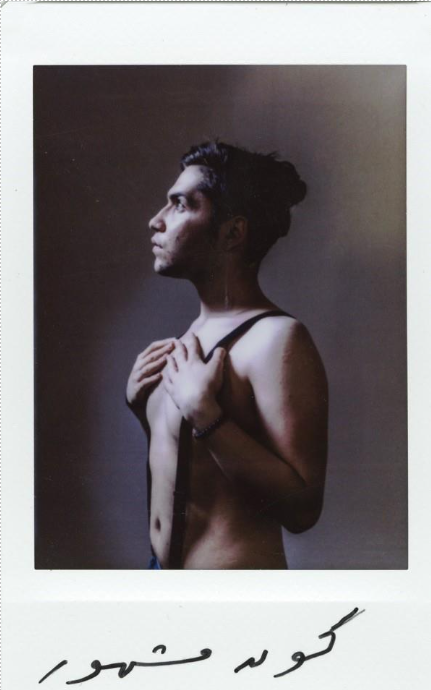

British photographer and journalist Bradley Secker (born 1987) likewise engages with and resists the claims to objectivity and reliance on stereotypes inherent in the kinds of ethnographic projects discussed by Stallabrass. His series SEXugees comprises dozens of small-scale, Instax Mini prints, which depict gay and trans individuals from Syria, Iraq, and Iran who were displaced to Turkey to flee war and persecution. These former students, engineers, and cleaners were unable to find jobs conventionally understood to align with their educational and professional training. They therefore turned to sex work, which they found to be one of the few sources of stable income available to them. Reminiscent of so-called “tart cards,” which arose in the 1960s United Kingdom as a covert means to solicit sexual services, Secker’s use of the Instax mini print, a form of Polaroid, is steeped in a history of consumer and transactional relations. This nature of the Polaroid is undoubtedly one aspect that attracted artists like Andy Warhol and Robert Mapplethorpe, who established the Polaroid’s status in the canon of queer visual culture. Its tactile quality and easy, immediate distribution has long made the creation of Polaroids a favorite social activity.30 The materiality of the Polaroid process and its intimacy of scale give the resultant photograph an almost bodily presence, as Nat Trotman evocatively suggests: “The pictures have interiors, viscous insides of caustic gels that make up the image itself. Users are warned not to cut into the objects without protective gloves—these photographs can be wounded, violated. Their frame protects and preserves them like clothing around a vulnerable body.”31 This process also ensures that the photographs are unique objects.

This singularity and fragility of the photographic object maps onto Secker’s broader conceptual interests in precarity and vulnerability, which he frames as a more complex and multilayered phenomenon than pure victimhood. Motivated by a sense of urgency to document and collect stories, Secker began this work in 2010 following a trip to Syria, where he noted the prevalence of gay men from Iraq who had fled to Damascus.32 Across several different projects spanning the past decade and a half, Secker has taken a keen interest in the social, economic, and political complexities that confront LGBTQ-identifying displaced persons who have moved to and/or sought asylum in Syria, Turkey, and across Europe. In addition to making images, a significant part of Secker’s work involves hearing and relaying stories, some of which convey traumas that can be difficult even to record.33

Crafting his SEXugees series in 2016, Secker documented in small part the effects of the immense refugee crisis brought on by the civil war in Syria, during which millions of people of Syrian and other nationalities were both internally and internationally displaced. Italian philosopher and political theorist Giorgio Agamben identifies the refugee as one embodiment of his concept of “homo sacer (sacred man),” which he characterizes as “human life . . . included in the juridical order [ordinamento] solely in the form of its exclusion (that is, of its capacity to be killed).”34 Agamben invokes the image of the Rwandan child, depictions of whom proliferated during the Rwandan Civil War (1991–1994) and attendant Rwandan Genocide (1994). Had Agamben been writing at the same time Secker was making his series, we might expect to read the author reference the image of the Syrian child in a desperate Mediterranean crossing; if writing in 2025, Agamben might have referenced the Palestinian child, starving, sick, and orphaned amid the ruins of Gaza. For years referred to as “the world’s largest open-air prison,” Gaza brings to mind in fact Agamben’s point that the Nazi concentration camp was far from an historic aberration but rather epitomized “the biopolitical paradigm of the West.”35 Pushing Agamben’s conception further, Achille Mbembe contends that “[t]he most accomplished form of necropower is the contemporary colonial occupation of Palestine,” arguing that “[t]he state of siege . . . allows for a modality of killing that does not distinguish between the external and the internal enemy. Entire populations are the target of the sovereign.”36 As Secker himself has seen firsthand, it was an analogous state of siege in Iraq that drove millions to seek refuge in Syria and, following the conflict and devastation there, subsequently in Turkey.37

Addressing the refugee specifically, Agamben ruminates: “If refugees…represent such a disquieting element in the order of the modern nation-state, this is above all because by breaking the continuity between man and citizen, nativity and nationality, they put the originary fiction of modern sovereignty in crisis.”38 Agamben goes so far as to term the refugee “the limit concept that radically calls into question the fundamental categories of the nation-state.”39 The young individuals who populate the SEXugees series inhabit three positions, which subject them to violence and insecurity: refugee, queer, and sex worker. In different but intersecting ways, these three situated positions also represent a challenge to the techniques of control by the nation-state. At the time he was seeing through this project, Secker observed that in Istanbul, where the project unfolded, the sex work industry was dominated by female-presenting workers yet had seen an increase in LGBTQ-identifying practitioners.40 Artists’ captivation with the figure of the female-presenting sex worker has long been a motif in European art, rising to greater prominence with the advent of modernism by the last half of the nineteenth century, when the traffic in women’s bodies provided an imaginative locus of heterosexual male desire and illicit sexual/economic relations that flouted bourgeois ideals of family and propriety.41 More than indulging in erotic fantasy or seeking out provocative subject matter, Secker impels us to see the people who currently occupy a certain role, making us aware that they have names—Dea, Mark, Ammar—along with individual perspectives, hopes, and fears.

Zaman and Secker both mobilize viewers’ empathy as a way to resist their subjects’ consignment to homo sacer or “human life . . . included in the juridical order . . . solely in the form of its exclusion.” While their photographic practices are formally and conceptually different, both frame empathy as more than a mode of interpersonal relations but as a radical political position. Even several years later, their work has lost none of their relevance. At the time of this writing, numerous state laws and a presidential executive order are aimed to eliminate trans rights if not transness entirely. Meanwhile, the devastation in Gaza wrought by the state of Israel’s military forces has spread to Syria (and Lebanon) in a new phase of the conflict with which Secker was engaging in 2016 and earlier. As the two photographers represent individuals and communities targeted by national and international policies, both negotiate between visibility in the service of public awareness and concerns for safety that such visibility raises. Visibility, on the one hand, can be empowering and is an important component to building empathy. Meanwhile, the ability to know and apprehend individuals and populations has long been a tool of the nation-state.

Zaman and Secker engage critically with both the medium of photography and the process of classification as mechanisms of ideology and domination, which date to the nineteenth century if not earlier. For Zaman, establishing a rapport with each person was critical. In writing about American Boys, Zaman affirms the importance of partnership, conceiving of their role as more of a conduit of a person’s message than as an author of an image.42 While we can’t see the photographer, we can still intuit an implicit trust and comfortability through the expressions and mannerisms of the photographed individual. The portraits throughout the series are tender and immediate, at times joyful, funny, confident, and self-assured. The photographs in Secker’s SEXugees series are also inscribed with statements from each of the subjects as well as their typical fees. In a way analogous to Zaman’s, Secker makes multiple images of each sitter, situated in different poses, with different lighting, and from different vantages, visual strategies that together create a sense of a “whole person.” Through these means, the sitters reclaim their bodies and highlight the tensions between empowerment and employment, expression and objectification. Despite or perhaps because of the small scale of the Polaroids, the images draw the viewer into an intimate optical relationship. The photographs’ dramatic chiaroscuro, along with the figures’ otherworldly gazes, and the images’ overall lack of context, lend the subjects a sense of timelessness and gravitas that contrasts to their otherwise precarious circumstances. The photographs’ subsequent placement on museum or gallery walls, with each individually framed and on view alongside other works of art, transforms them from portable and transactional objects into images that demand serious aesthetic contemplation.

Zaman and Secker are not the only artists included in Irreplaceable You who explore the pictorial and political dimensions of empathy; others might include Alfredo Jaar, Berlinde de Bruyckere, and Chan Chao, to name a few. Hopefully, their work will move visitors to ponder some of the complex questions empathy poses for art. A first and fundamental question might be: does art have the capacity to convey another person’s perspective in a full sense? Significantly, Zaman and Secker question whether a museum provides the necessary conditions to establish such a visual and/or mental relationship with a work of art. There are certainly contexts for the display of art where the cultivation of empathy is either not considered or is invoked primarily as a marketable feature, for example, the art gallery and art fair. At present, you are likely encountering these works of art in the context of a museum exhibition, where the aims of education and edification balance (ideally) against commodification and spectacle, the latter of which are perhaps more readily promoted in commercial art contexts. If an individual work of art or a series is meant to help us identify with the feelings or mental states of other people, does it need to be figural, that is, does it need to depict obviously human subjects? Does one need textual interpretation; for instance, does one need to know the person’s name or story? It’s telling that the examples to which I turned in this section are photographic series that include textual framing. Questions like these reveal the intricate webs of optical and power relations that take shape between the work of art and its viewers, the work of art and its maker, and viewers and maker. Again, this project surfaces and grapples with these kinds of questions, inviting a discussion about them rather than providing definitive answers to them.

The Dignifying Power of Art

In addition to empathy, another way artists frame visitors’ engagement with personhood in Irreplaceable You is through visual strategies of dignification. Dignity is likewise situational and ever shifting and has its own fraught relationship with history and power, as addressed above. In the long tradition of European and American portraiture, prestige and status are often signified through visual markers such as the sitter’s pose, facial expression, clothing, hairstyle, accoutrements, and setting, often commensurate with the subject’s class and race (although, there are notable exceptions). These kinds of portraits, for example, Robert Feke’s portrait of Samuel Waldo (ca. 1748), are popularly thought today to be about advertising the individual’s power and wealth. The truth is portraits are more complicated than that; they are also markers of social and familial networks, the sitter’s own self-conception, the artist’s “signature style,” and local and global historical forces. Large, full-length portraits like that of Waldo also declare their subject’s importance through their very scale and materiality. Even while museums contend with the problematic legacies of many of the people honored in these portraits, the physical fact of the work of art still fills space and commands attention.x43

In terms of subject matter, most of the works of art featured in Irreplaceable You have little in common with Feke’s portrait of Waldo. I bring in this example to convey how pictorial traditions (like portraiture) and institutions (like museums), especially in Euro-American, “Western” contexts, have long been at work establishing and defending art’s special status amid other forms of visual-cultural production like the illustrated press, commercial film, and social media.44 We might return to the words of Mbembe, who provocatively but rightfully declares that “since the modern age the museum has been a powerful device of separation.”45 He expounds:

The exhibiting of subjugated or humiliated humanities has always adhered to certain elementary rules of injury and violation. And, for starters, these humanities have never had the right in the museum to the same treatment, status, or dignity as the conquering humanities. They have always been subjected to other rules of classification and other logics of presentation.46

Here, Mbembe not only reminds us that classification is one of the most fundamental techniques of museums as institutions, but he also recalls Michel Foucault’s thesis that classification is a tool of (modern, state) power. What is more, Mbembe calls out how museums have, even down to their normative techniques of cataloguing and display, positioned certain histories, cultures, and traditions as worthy of serious study and respect while omitting or excluding others. Such interpretive inequities are the extension and continuation of the physical and geopolitical violences inflicted by the colonial order that in large part brought into being the modern museum as we know it today.

Mexican painter Sergio Miguel defies long-standing art-historical and social rules of classification, blurring the boundaries between Mbembe’s “subjugated or humiliated humanities” and the “dignity [of] the conquering humanities.” In his full-length portrait Jacinta (2022), Miguel fuses the history of painted portraits with another colonial art practice, the genre known as ángel arcabucero (arquebusier angel). The genre emerged in seventeenth-century Peru as a melding of artistic practices under Spanish colonial rule, comprising elements from pre-Hispanic, Indigenous, and Spanish Catholic pictorial traditions. Miguel further combines this form with the full-length oil portrait, which, as discussed in the case of Samuel Waldo, has long served to buttress a social hierarchy predicated on wealth, violence, and oppression. Miguel inserts full-length likenesses of his queer, femme, Latinx friends into these art-historical genealogies, reclaiming forms of artmaking closely tied to European colonization. In so doing, Miguel also calls attention to the many historical and enduring exclusions in Euro-Americentric canons of art. The scale of Miguel’s painting, which approaches that of Feke’s portrait of Waldo, ensures that Jacinta cannot be passed by or overlooked.

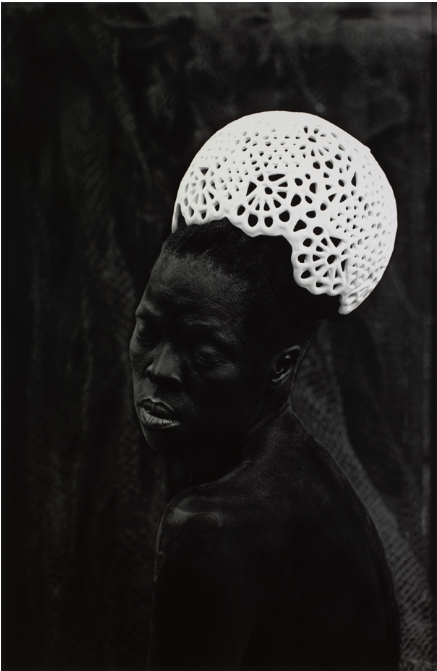

In a similar gesture, South African activist and artist Zanele Muholi (born 1972) uses their own likeness to advocate for a numberless crowd of Black women, queer, femme, nonbinary, and trans individuals who have been historically excluded from the same Euro-Americentric canons of art. Sine IV, Melbourne, Australia(2020), is part of the larger self-portrait project Somnyama Ngonyama (isiZulu for “Hail the Dark Lioness”), which the artist began in 2012.47 In several photographs throughout this series, Muholi dons everyday objects and materials as though they constituteceremonial regalia. For instance, in Sine IV, a decorated white bowl or vase becomes a sort of crown, whereas in other works, towels, sheets, gourds, and even a glass lampshade are transformed into various kinds of headdresses, and materials like Styrofoam, rubber tires, and miners’ hats and goggles become their own forms of bodily ornament. Through Muholi’s reworking, such mundane objects come to reference moments of violence and discrimination in the artist’s own life in addition to labor strikes violently suppressed by police and the system of apartheid more broadly. Through these photographs, Muholi creates alter egos with different Zulu names but also new archetypes by combining Western pictorial conventions with references to South African politics. The series proclaims, in the artist’s own words, “Just like our ancestors, we live as Black people 365 days a year, and we should speak without fear.”48 Muholi inhabits both artist and model; meanwhile, their pyramidal form, mournful expression, and stark tonal shifts in Sine IV make use of formal conventions meant to establish a sense of the beautiful. But Muholi overturns the very standards of beauty with which they engage, manipulating their own skin tone in the photograph to appear darker, thereby playing against racist and colorist tropes that have contributed both to historic and contemporary exclusions.49

Miguel and Muholi, as with most of the artists in Irreplaceable You, are concerned with more than just instrumentalist notions of inclusion, visibility, and representation. Or rather, the artists presented here are concerned with these notions insofar as they have real-life stakes. Several of the artists advocate—through their practice, education, journalism, and activism—for individuals and groups whose very humanity has been contested, not just their status (or lack thereof) in museums and canons of art history. Mounting backlash against “diversity, equity, and inclusion” in recent political discourse and governmental policies mobilizes a form of nostalgia that invokes a deeply (and deliberately) divisive mythology of untroubled white supremacy, homogenous and free from all the clamoring by “the Other” for rights and entitlements, including the right to exist. All this unfolds against the backdrop of a social order that already treats life as disposable, making a spectacle out of violence and cruelty and blurring the lines between fiction and reality.50 It feels bleak, and the artists here do not offer viewers rose-colored glasses. Instead, by using the various pictorial, material, and conceptual means at their disposal, these artists (and many others) offer means of resistance, provide platforms to protest systemic violence and oppression, and center the marginalized and vulnerable.

Parting Thoughts

As a final reflection, I want to call up Mbembe’s concept of the “anti-museum.” He describes it as follows:

As for the anti-museum, by no means is it an institution but rather the figure of another place, one of radical hospitality. A place of refuge, the anti-museum is also to be conceived as a place of unconditional rest and asylum for all the rejects of humanity and the “wretched of the earth,” the ones who attest to the sacrificial system that will have been the history of our modernity—a history that the concept of archive struggles to contain.51

I can’t claim that Irreplaceable You constitutes the kind of “anti-museum” that Mbembe calls for. The project does make interventions throughout the Museum galleries, seeking to disrupt the surety and categorizing impulse of the archive if still contained within it. Space is also carved out for reflection and respite, aspiring to if not fully achieving Mbembe’s poignant call for “unconditional rest and asylum,” a call that grows ever more urgent. As with any exhibition, the works of art are only part of the matrix of representation. The visitors’—your—presence in the space along with all the lived experiences, backgrounds, and senses of self that you bring into conversation with the works of art on the walls or on pedestals activate and complete this project. With that in mind, Irreplaceable You invites us to think together: what would a place of “radical hospitality” look like? Could an institution like the Bowdoin College Museum of Art or even Bowdoin College itself fill this role, or would a new paradigm need to be established for it? It is with this final set of questions that I leave you.

Sean Kramer is the Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. His scholarly and curatorial interests have bridged the nineteenth century and the present, connected by threads of gender, power, and violence. At the BCMA, he organized the exhibition Irreplaceable You: Personhood and Dignity in Art, 1980s to Now, which bring together twenty-seven contemporary artists whose work responds to dehumanization and dispossession by the media, political rhetoric, and art-historical canons. Concurrently, he is developing a book manuscript that examines the rise to prominence of the motif of the common soldier in French and British art and culture from the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 until the start of World War I in 1914. In addition to the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Sean has held curatorial, education, and research positions at the Detroit Institute of Arts, the University of Michigan Museum of Art, and the Spencer Museum of Art in Lawrence, Kansas, and was the recipient of a Visiting Scholar Award from the Yale Center for British Art. He completed his PhD in the history of art at the University of Michigan in 2022 and has an MA and BA in art history from The University of Kansas. Beginning in Fall 2025, Sean will be teaching museum studies in the Art History and Architecture Department at the University of Pittsburgh.

[1] “Universal Declaration of Human Rights, General Assembly of the United Nations, resolution 217 A (III),” in Transforming Terror: Remembering the Soul of the World, eds. Karin Lofthus Carrington and Susan Griffin (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2019), n.p., ProQuest Ebook Central.

[2] Angie Morrill, Eve Tuck, and the Super Futures Haunt Qollective, “Before Dispossession, Or Suriving It,” Liminalities:A Journal of Performance Studies 12, no. 1 (2016), 2.

[3] This has been a recurring issue for Butler. See, for instance, Judith Butler, Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? (New York: Verso, 2009).

[4] For example, The Intercept reported a demonstrable bias against Palestinians by major publications, and NPR noted the extreme polarization of the coverage. Adam Johnson and Othman Ali, “Coverage of the Gaza War in The New York Times and Other Major Newspapers Heavily Favored Israel, Analysis Shows,” The Intercept, January 9, 2024; Carrie Kahn and Greg Dixon, “Israelis and Palestinians are in Separate Media Realities,” NPR, May 6, 2024.

[5] Numerous journalists and commentators in the few years have pointed out a seeming fixation on Black death and suffering in the United States. See, for instance, Wesley Lowery, “Why There Was No Racial Reckoning,” The Atlantic, February 8, 2023; Anthony Conwright, “Videos of Police Brutality against Black People Are a Futile Spectacle in White America,” The New Republic, February 3, 2023; Savala Nolan, “Americans Need to Examine their Relationship to Images of Black Suffering,” Time, May 25, 2022; Elisha Tawe, “Black Death Spectacle: Cinema, Surveillance, and Black Trauma,” MUBI, September 3, 2021; and Elizabeth Alexander, “Endless Grief: The Spectacle of ‘Black Bodies in Pain,’” The New York Times, June 19, 2020.

[6] Another project at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art to investigate this question was This Is a Portrait if I Say So: Identity in American Art, 1912 to Today; see Anne Collins Goodyear, Jonathan Frederick Walz, and Kathleen Merrill Campagnolo, This Is a Portrait if I Say So: Identity in American Art, 1912 to Today (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016).

[7] Personhood has formed the subject of study for philosophers, theologians, anthropologists, sociologists, psychologists, and legal scholars. While scholars in these disciplines have approached the concept in different ways, there remains a sense that personhood, at least as it is understood in the West, has been largely shaped by Roman theatrical and legal traditions, Christian theology, and a capitalist focus on individuality. The literature is too extensive to give a comprehensive bibliography here. Some references I found helpful include: Fraser Watts and Marius Dorobantu, “AI Relationality and Personhood,” Zygon (2023): 1–16; David J. Gunkel, “Debate: What Is Personhood in the Age of AI?,” AI & Society 36, no. 2 (June 2021), n.p.; J. Wentzel Van Huyssteen and Erik P. Wiebe, In Search of Self: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Personhood (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 2011); John Christman, “Narrative Unity as a Condition of Personhood,” Metaphilosophy 35, no. 5 (October 2004): 695–713; Michael Carrithers, Steven Collins, and Steven Lukes, eds., The Category of the Person: Anthropology, Philosophy, History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985). Anthropologists have of course examined constructions of personhood in non-Western societies. See, for instance, Chris Fowler, The Archaeology of Personhood: An Anthropological Approach (Oxford: Routledge, 2004).

[8] For instance, the state’s regulation of movements, behaviors, and wellbeing of individuals and populations has formed the central point of inquiry in the study of “biopolitics” ever since the concept was elaborated on by French historian and theorist Michel Foucault in the 1970s. Thomas Lemke astutely noted that Foucault’s characterization of “biopolitics” shifted across his writings. At times, Foucault instead used the term “biopower.” Thomas Lemke, Biopolitics: An Advanced Introduction, trans. Eric Frederick Trump (New York: New York University Press, 2011), 34. Foucault’s analysis of institutions like the prison, school, and hospital as mechanisms of control can be found in, for instance, Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1995); and The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception (New York: Vintage Books, 1975).

[9] Gunkel, “Debate,” n.p.

[10] Merriam-Webster.com, s.v. “dignity,” accessed August 5, 2024, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/dignity.

[11] The central texts on which I draw include Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1995); Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (New York: Verso Books, 2004); Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? (New York: Verso, 2009); The Force ofNonviolence: An Ethico-Political Bind (New York: Verso, 2020); and Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019). Each of these authors have engaged with one another and have driven a range of responses in different disciplines.

[12] Scholar Thomas Keenan, in his work on the visualization of violence, examined the proliferation and limits of imagery of atrocity to effect social and political action during the Bosnian War of the early 1990s: “Among the too many would-be ‘lessons of Bosnia,’ this one stands out for its frequent citation: that a country was destroyed and genocide happened, in the heart of Europe, on television, and what is known as the world or the West simply looked on and did nothing.” Thomas Keenan, quoted in Brianne Cohen, Don’t Look Away: Art, Nonviolence, and Preventive Publics in Contemporary Europe (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2023), 2.

[13] Maggie Nelson, The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning (National Geographic Publishers, 2012), 31.

[14] Ibid., 29.

[15] Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle (Detroit: Black & Red, 1983); and Jean Baudrillard, “The Gulf War: Is It Really Taking Place?,” in The Jean Baudrillard Reader, ed. Steve Redhead (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008), 102.

[16] Judith Butler, Force of Nonviolence, 2.

[17] Neuroscientist Jamil Zaki has cited separate studies, for instance, where agents of mass slaughter and genocide as well as executioners both reported shutting down their sense of empathy and constructing ideas of their victims as less than human. Jamil Zaki, War for Kindness: Building Empathy in a Fractured World (New York: Crown, 2019), 25.

[18] See Serubiri Moses, ed., Reza Aramesh: Action: By Number (Milan: Skira, 2024).

[19] For instance, a solo exhibition by the artist Shaun Leonardo closed at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Cleveland, Ohio, following backlash over his frank representation of police violence. Leonardo, for his part, pointed out that the museum never consulted him about the controversy or asked him to engage with their constituent communities. See Brian Boucher, “A Museum Canceled a Show about Police Brutality. Here's the Art,” The New York Times, June 9, 2020.

[20] Butler, Frames of War, 8.

[21] Zaki, War for Kindness, 21.

[22] Ibid., 56–63.

[23] Mbembe, Necropolitics, 2.

[24] Ibid., 2–3.

[25] Ibid., 7.

[26] Ibid., 3.

[27] See Soraya Zaman, American Boys (Daylight Books, 2019).

[28] Stallabrass articulates this phrase in regard to photographers like Rineke Dijkstra and Diane Arbus, whom the author then placed in a genealogy through documentary and fashion photographers, including Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, August Sander, and others. Julian Stallabrass, “What’s in a Face? Blankness and Significance in Contemporary Art Photography,” October 122 (Fall 2007): 71–90.

[29] Ibid., 87.

[30] Nat Trotman, “Life of the Party: The Polaroid SX-70 Land Camera and Instant Film Photography,” Afterimage 29, no. 6 (May/June 2002): 10.

[31] Nat Trotman, quoted in Peter Buse, “The Polaroid Image as Photo-Object,” Journal of Visual Culture (2010): 190.

[32] Nicole Bogart, “Bradley Secker—Portraying the Lives of Displaced LGBT Individuals Through Photojournalism,” Salzburg Global Seminar, July 7, 2017, web.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Agamben, Homo Sacer, 8.

[35] Agamben, quoted in Lemke, Biopolitics, 53. The phrase “world’s largest open-air prison” has been often repeated in the press. For a brief overview of the history of Gaza, see an interview published through National Public Radio (NPR) between host Scott Simon and analyst Tahani Mustafa. Scott Simon and Hadeel Al-Shachi, “Gaza Is Called an Open-Air Prison. How Did It Get to This?,” November 4, 2023, web.

[36] Mbembe, Necropolitics, 82. An artist who has engaged with empathy in relation to the Palestinian diaspora is Emily Jacir. For the series Where We Come From (2001–2003), Jacir reached out to Palestinian friends and acquaintances across the diaspora in Europe, the United States, and the West Bank and asked them the question: “If I could do anything for you, anywhere in Palestine, what would it be?” She then used photographs to document herself fulfilling these requests, which she was able to do by virtue of her American passport. This work informed the conception of Irreplaceable You in important ways. Unfortunately, however it was not possible to procure loans from this series for the exhibition. For a fuller discussion of this series, see T.J. Demos, “Desire in Diaspora: Emily Jacir,” Art Journal 62, no. 4 (Winter 2003): 68–78.

[37] Bogart, “Bradley Secker.”

[38] Agamben, Homo Sacer, 131.

[39] Ibid., 134.

[40] Bogart, “Bradley Secker.”

[41] For an in-depth analysis of the pictorial, social, and political dynamics around the depiction of female sex work in nineteenth-century French art, see Hollis Clayson, Painted Love: Prostitution in French Art of the Impressionist Era (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991).

[42] Zaman explains this process in an interview with Emma Specter, “Photographer Soraya Zaman’s American Boys Series Tells a New Story about Masculinity,” Vogue, February 10, 2022.

[43] The current wall gallery label makes plain that Waldo achieved his great wealth through enslavement, and he also forcibly displaced thousands of Wabanaki people in present-day Maine to establish the so-called “Waldo Patent.”

[44] In the 1930s, Walter Benjamin analyzed this phenomenon amid the simultaneous rise of commercial capitalism in the United States, Nazism in Germany, and Stalinism in the Soviet Union. He developed the idea of the “aura” of the work of art, which has had a major impact in both art history and media studies in thinking about how culture is both disseminated and contested. Benjamin was rather ambivalent about the idea of the “aura,” seeing it as a bourgeois mysticism that replaced religious mysticism while also seeming to decry its passing with the advent of mass media. See, Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproducibility,” in Selected Writings Volume 3, trans. Edmund Jephcott, Howard Eiland, and others; eds. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 2002), 101–133.

[45] Mbembe, Necropolitics, 171.

[46] Ibid.

[47] For more on this series, see Renée Mussai, Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness (New York: Aperture, 2018).

[48] Zanele Muholi, quoted in Ray Mark Rinaldi, “Zanele Muholi is ‘Reclaiming my Blackness’ with Powerful Self-Portraits at Denver’s Center for Visual Art,” The Denver Post, January 19, 2021.

[49] Hlonipha Mokoena, “Dark Magus,” in Zanele Muholi, 148.

[50] Brad Evans and Henry A. Giroux, Disposable Futures: The Seduction of Violence in the Age of Spectacle (San Francisco: City Light Books, 2015).

[51] Mbembe, Necropolitics, 172.